What does our brain see in architecture?

Of all our senses, vision has the greatest influence on how we experience buildings. From light and colour to form and pattern, what we see shapes what we feel. At XUL, we use this understanding to design spaces that not only look beautiful but also feel intuitive, engaging, and emotionally supportive for the people who live and work in them.

At a glance:

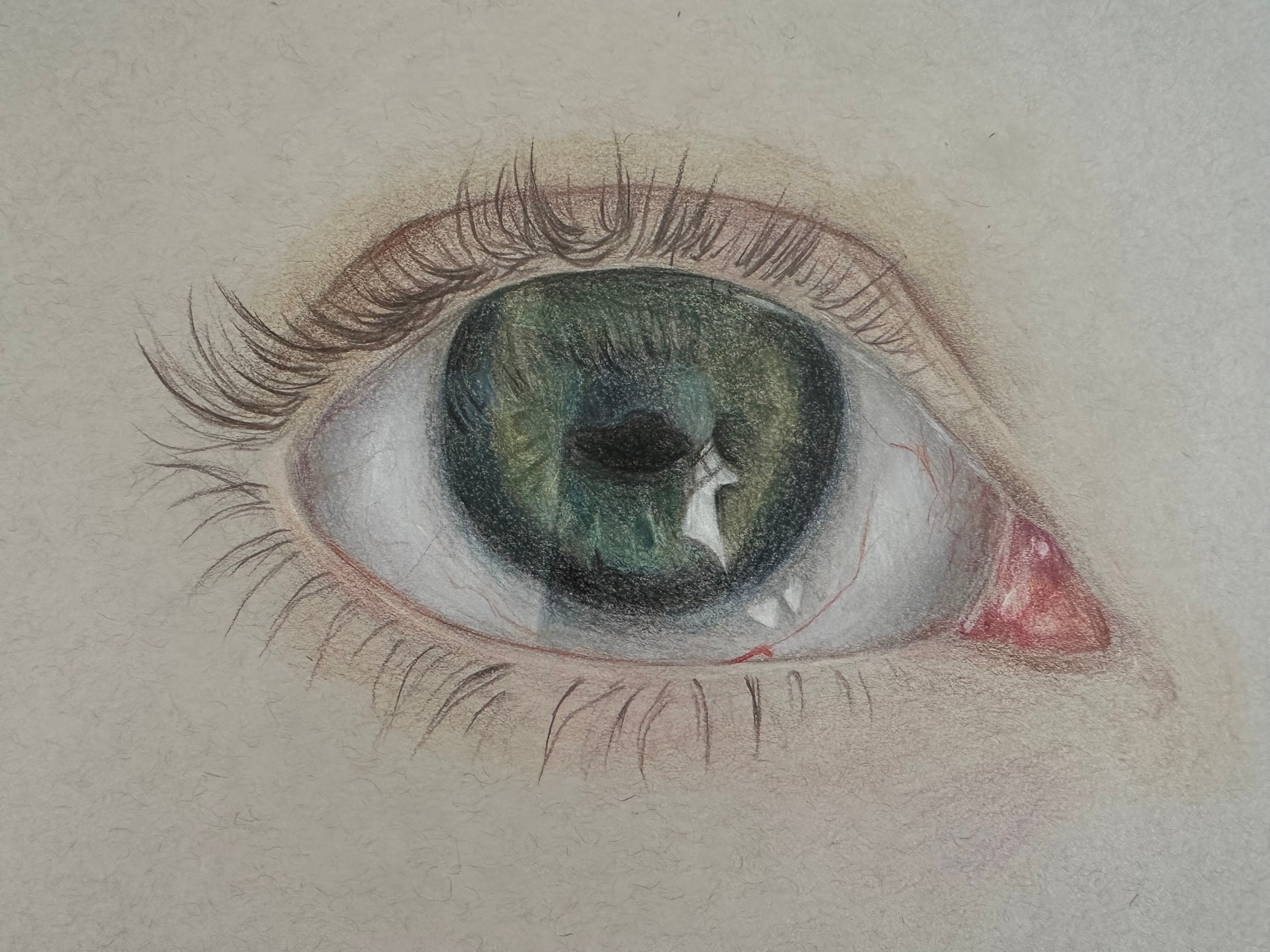

- Our brain processes visual information in fast, layered stages – contours, lightness, then colour.

- The parahippocampal place area helps us emotionally connect with spaces.

- We’re drawn to structured complexity; facades with texture, contrast, and variation.

- Design features like ceiling height, curvature, and visual patterns affect comfort and behaviour.

- Visual cues guide how we move through a space, supporting wayfinding and wellbeing.

How does the brain make sense of what we see?

Visual processing happens fast and in stages. First, the brain picks up basic outlines and shapes. Then it works out brightness, and finally, colour. Even when we don’t get the full picture, our brain quickly fills in the gaps, especially when safety is uncertain. That’s why a dim corridor might feel uneasy, even if it’s perfectly safe (Abbas et al., 2024).

A key part of this process happens in the parahippocampal place area, a brain region tuned into scenes and spatial layouts. It helps us recognise different environments and even builds emotional ties to them. This explains why some spaces feel instantly familiar or calming (Abbas et al., 2024).

Why do some buildings feel cold or forgettable?

A lot of it comes down to visual attention. We don’t take in everything we see equally, but rather our eyes are naturally drawn to certain features. Studies using eye-tracking have shown that flat, minimalist facades often fail to hold our attention. They lack the kind of detail and variation our brains crave, which can sometimes lead to a low-level stress response (Salingaros & Sussman, 2020).

On the other hand, buildings with complexity and strength, such as rich textures, strong contrasts, or repeating elements, feel more inviting. This is because complexity invites visual exploration, while strength, for example, symmetry, boldness, and balance, keeps us engaged (Lee and Ostwald, 2022).

How does what we see affect how we move?

On top of helping us take in our surroundings, vision shows us how to use them. This is where visual affordances come in. These are design cues that reflect their function; open stairs imply “go up,” benches say “sit here,” and a wide hallway subtly directs us to move forward (Young & Cleveland, 2022).

Designers can use these cues to make spaces easier to understand without relying on signs. Features like visible exits, framed views, and natural lighting help our brains build internal maps. This supports wayfinding and helps us feel more confident navigating unfamiliar spaces (Øien et al., 2023).

Why do some places just feel “right”?

Much of our response is subconscious. Just as we can be drawn to a friendly face, we’re drawn to environments that are visually appealing. Psychologists talk about three key qualities:

- Coherence – how easy the space is to read

- Fascination – how interesting or engaging it is

- Hominess – how personally inviting it feels

When a space scores high on all three, it feels more comfortable and emotionally rewarding (Coburn et al., 2020). This matters because the more we feel at ease in a space, the more likely we are to want to spend time in it.

Final Thoughts

From how we process shapes and colours to how we navigate the world around us, vision plays a central part in how we experience architecture. Designs that align with how the brain interprets visual information, offering clarity, complexity and intuitive cues, can create spaces that are not only beautiful but feel good to be in. When we design with vision in mind, we create environments that truly see us back.

References

Abbas, S., Okdeh, N., Roufayel, R., Kovacic, H., Sabatier, J.-M., Fajloun, Z., & Abi Khattar, Z. (2024). Neuroarchitecture: How the Perception of Our Surroundings Impacts the Brain. Biology, 13(4), 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology13040220

Coburn, A., Vartanian, O., Kenett, Y. N., Nadal, M., Hartung, F., Hayn‑Leichsenring, G., Navarrete, G., Gonzalez-Mora, J. L., & Chatterjee, A. (2020). Psychological and neural responses to architectural interiors. Cortex, 126, 217–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2020.01.009

Øien, T. B., Grangaard, S., & Lygum, V. L. (2023). Exploring the dynamics of architecture with the concept of affordance. Philosophical Psychology, 37(7), 1858–1877. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2023.2273400

Salingaros, N., & Sussman, A. (2020). Biometric pilot-studies reveal the arrangement and shape of windows on a traditional façade to be implicitly “engaging”, whereas contemporary façades are not. Urban Science, 4(2), Article 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci4020026

Young, F., & Cleveland, B. (2022). Affordances, architecture and the action possibilities of learning environments: A critical review of the literature and future directions. Buildings, 12(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12010076